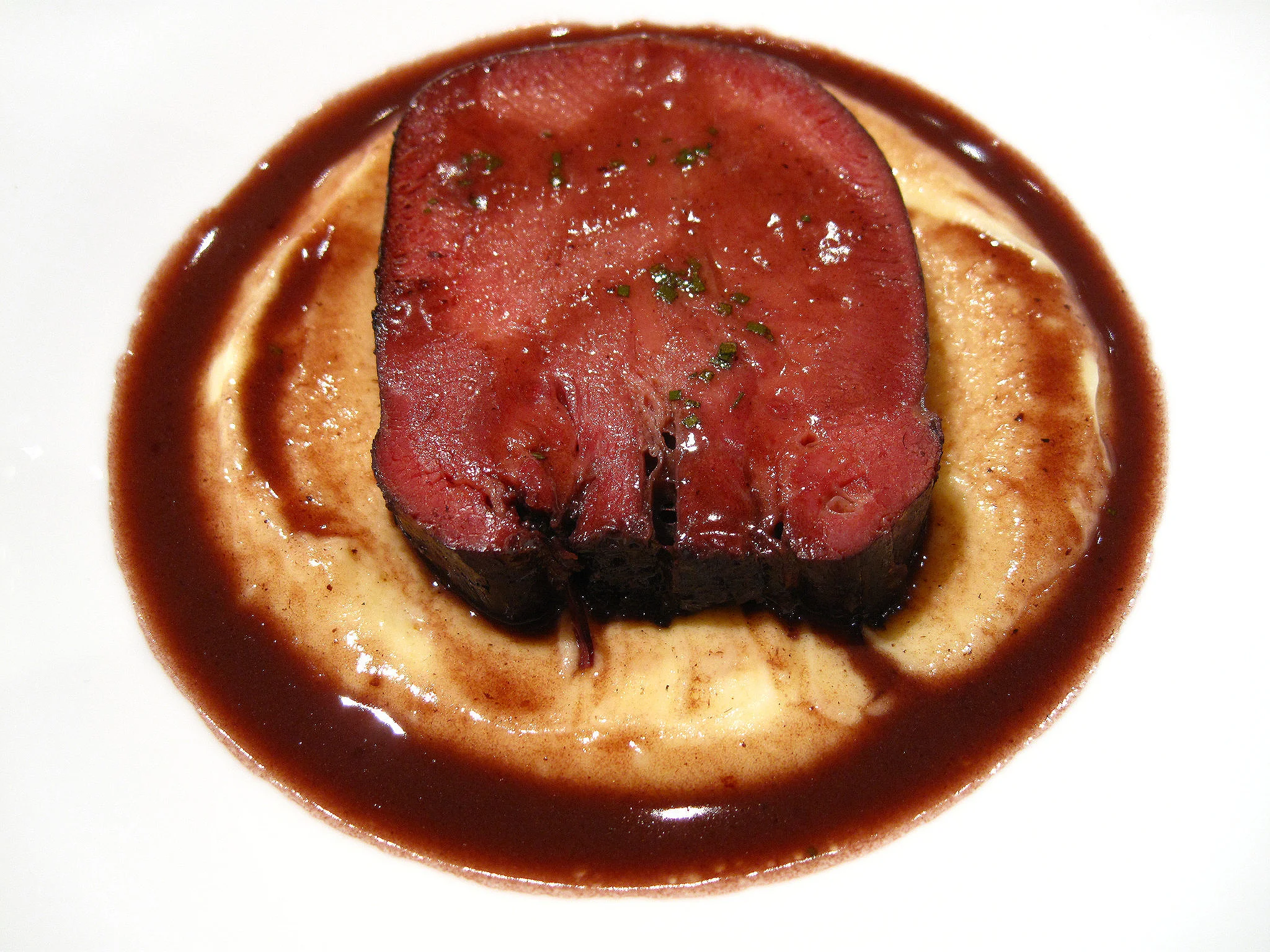

I've been in Montreal for just over two weeks now and when I haven't been coding, I've been eating. The one place I find myself returning to almost daily -- sometimes even twice a day -- is a small cafe around the corner from where I'm staying. Its name is Cafe Myriade, and it has the best coffee in the city. Myriade is owned and operated by Canadian National Barista Championship finalist Anthony Benda and his business partner Scott Rao author of The Professional Barista's Handbook. Its drip coffee, espresso, cappuccino, macchiato, eva solo, and french press are nonpareil. Its syphon coffee is also at the top because, well, it's the only place in the city that does it. But also important is the atmosphere, one that just makes you want to come back. Or, maybe that's the caffeine speaking. Probably both.

Hi.

Welcome to my blog. I document my adventures in food, travel, and coffee.